Version Control with Git

- Collaborating

Learning Objectives

- Explain what remote repositories are and why they are useful.

- Explain what happens when a remote repository is cloned.

- Explain what happens when changes are pushed to or pulled from a remote repository.

So far, we’ve seen how Version control can help us track the changes we make to our files, and to revisit any point in their history.

Git Workflow - Local Repo

(there are a few extra commands we haven’t covered today for you to look at).

But, version control really comes into its own when we begin to collaborate with other people.

The missing link

We already have most of the machinery we need to do this; the only thing missing is to copy changes from one repository to another.

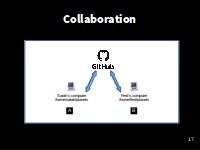

Collaboration

Systems like Git allow us to synchronise work between any two repositories.

In practice, though, it’s easiest to use one copy as a central hub, and to keep it on the web rather than on someone’s laptop.

Many programmers use hosting services like GitHub or BitBucket to hold those master copies; we’ll explore the pros and cons of these a bit later.

Exploring the collaborative process

But first let’s explore the collaborative process. Time to buddy up.

Collaboration

So far we have been working in splendid isolation. We’re going to use GitHub to set up a remote repository and start “collaborating” with our partners.

Developer A is going to take the role of the project originator. Developer B is going to take now on the role of a colleague joining the project and collaborating in development.

With the help of two terminals (opened in different directories on the same computer), I’ll be taking on both roles. In your pairs, decide who will be Developer A and Developer B while I get set up.

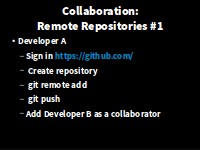

Developer A - To GitHub!

Remote Repositories #1

Now, Bs just sit back for a moment and watch A until told otherwise

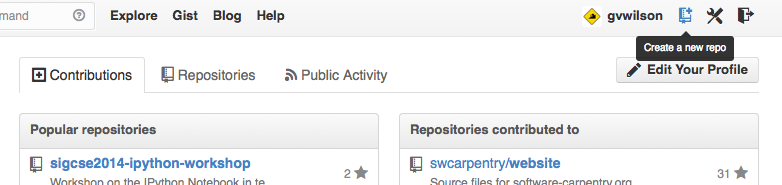

JUST A’s. Let’s start by sharing the changes we’ve made to our current project with the world. Log in to GitHub, then click on the icon in the top right corner to create a new repository called climate-analysis:

Creating a Repository on GitHub (Step 1)

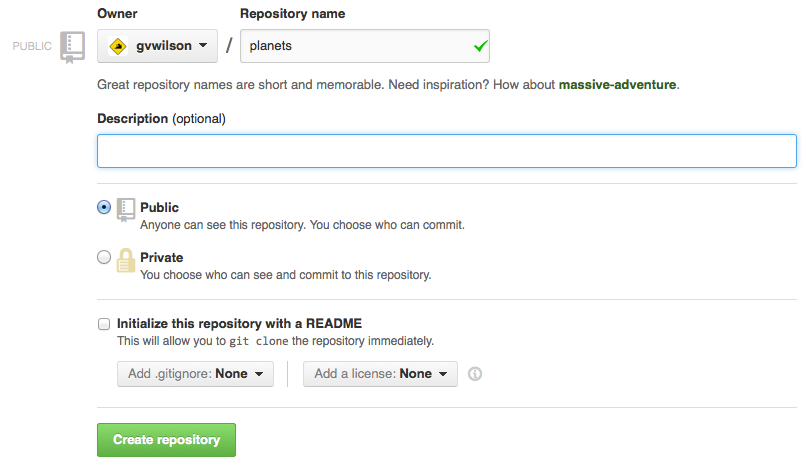

Name your repository “climate-analysis” You can optionally give it a friendly description and prove a README.md which is rendered on the front page of the web interface.

GitHub will host Publicly accessible repositories free of charge, but makes a charge for Private ones. BitBucket offers free private repositories for teams of up to 5.

You need to be sure that you really want to make your code publicly accessible, think about licensing, and that you’re not breaching the terms of any license of shared code by making it publicly available.

and then click “Create Repository”:

Creating a Repository on GitHub (Step 2)

Connecting the remote repository

Our local repository still contains our earlier work on climate-analysis.py and temp_conversion.py, but the remote repository on GitHub doesn’t contain any files yet:

The next step is to connect the two repositories.

We do this by making the GitHub repository a remote for the local repository. A remote is a repository conected to another in such way that both can be kept in sync exchanging commits.

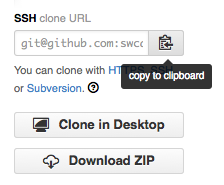

The home page of the repository on GitHub includes the string we need to identify it:

Where to Find Repository URL on GitHub

Copy that URL from the browser, go back to your local repository, and run this command using your repository name not mine:

$ git remote add origin https://github.com/js-robinson/climate-analysis.gitThe name origin is a local nickname for your remote repository: we could use something else if we wanted to, but origin is conventional, and will come in useful later.

The only difference should be your username instead of js-robinson.

We can check that the command has worked by running git remote --verbose:

$ git remote --verboseorigin https://github.com/js-robinson/climate-analysis.git (fetch)

origin https://github.com/js-robinson/climate-analysis.git (push)Push commits from local to remote

Once the remote is set up, we can push the changes from our local repository to the repository on GitHub:

$ git push origin masterCounting objects: 10, done.

Delta compression using up to 8 threads.

Compressing objects: 100% (10/10), done.

Writing objects: 100% (10/10), 1.47 KiB | 0 bytes/s, done.

Total 10 (delta 2), reused 0 (delta 0)

To https://github.com/js-robinson/climate-analysis.git

* [new branch] master -> masterThe push command takes two arguments, the remote name (‘origin’) and a branch name (‘master’).

We haven’t yet discussed branching yet, and we won’t go into it today, but basically.

Branching is a feature common to almost all version control systems and gives you the ability to diverge from the main line of development and to continue to do work without messing with that main line. The main (default) branch is the master.

At a later time you can re-integrate branches to the master.

So, for Developer A, our local and remote repositories are now in sync! You can check in your browser that the files have reached your GitHub repository.

Testing Pull

Still as Dev. A We can pull changes from the remote repository to the local one as well:

$ git pull origin masterFrom https://github.com/js-robinson/climate-analysis

* branch master -> FETCH_HEAD

Already up-to-date.Pulling has no effect in this case because the two repositories are already synchronized. If someone else had pushed some changes to the repository on GitHub, this command would download them to our local repository.

Lastly, let’s add Developer B as a collaborator on our project. Return to the repos GitHub page, and click the Settings link on the right, followed by the collaborators link on the left. Add Developer B with there GitHub username.

Developer B - Cloning the remote repository

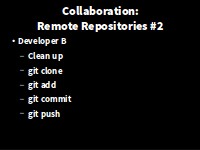

Remote Repositories #2

Now Developer B gets a go! - Developer A, you can take a break and watch.

First, we need to accept Developer A’s invitation to collaborate on GitHub. You will receive an email, but we can avoid the wait by logging into GitHub in our browsers, and visiting the invite link:

https://github.com/js-robinson/climate-analysis/invitationsThen, we need to move away from our own copies of the filse, to avoif confusion. Remember, in this example, Developer B is playing the role of a fresh collaborator on the project

$ cd$ git clone https://github.com/js-robinson/climate-analysis.gitCloning into 'climate-analysis'...

remote: Counting objects: 10, done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (8/8), done.

remote: Total 10 (delta 2), reused 10 (delta 2), pack-reused 0

Unpacking objects: 100% (10/10), done.

Checking connectivity... done.git clone creates a fresh local copy of a remote repository.

Let check what we’ve got:

$ cd climate-analysis

$ lsclimate_analysis.py temp_conversion.pyDeveloper B - Add rainfall_conversion.py

Lets expand our library of climate analysis functions by adding a new file:

$ nano rainfall_conversion.py

$ cat rainfall_conversion.py"""A library to perform rainfall unit conversions"""

def inches_to_mm(inches):

"""Convert inches to milimetres.

Arguments:

inches -- the rainfall inches

"""

mm = inches * 25.4

return mm$ git add rainfall_conversion.py

$ git commit -m "Add rainfall module"[master bcbf9be] Add rainfall module

1 file changed, 11 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 rainfall_conversion.pythen push the change to GitHub:

$ git push origin masterCounting objects: 4, done.

Delta compression using up to 8 threads.

Compressing objects: 100% (3/3), done.

Writing objects: 100% (3/3), 475 bytes | 0 bytes/s, done.

Total 3 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0)

To https://github.com/js-robinson/climate-analysis.git

dab17a9..bcbf9be master -> masterNote that we didn’t have to create a remote called origin: Git does this automatically, using that name, when we clone a repository. (This is why origin was a sensible choice earlier when we were setting up remotes by hand.)

Developer A - Pull in the changes

Remote Repositories #3

Developer A can now update their repository with the changes made by B:

[** Check Working Directory**]

$ git pull origin masterremote: Counting objects: 3, done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (3/3), done.

remote: Total 3 (delta 0), reused 3 (delta 0), pack-reused 0

Unpacking objects: 100% (3/3), done.

From https://github.com/js-robinson/climate-analysis

* branch master -> FETCH_HEAD

dab17a9..bcbf9be master -> origin/master

Updating dab17a9..bcbf9be

Fast-forward

rainfall_conversion.py | 11 +++++++++++

1 file changed, 11 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 rainfall_conversion.pyHey look: We’re collaborating!

Exercise: Two way collaboration

Now lets work it the other way. Developer A can add a brief README.md stating the authors of the package we’re developing (You), and describing its purpose “Tools to parse and convert climate data from CSV” Add / commit them to their local repository and push them to github. Developer B can pull the updates