Building programs with Python

Data Visualisation

Learning Objectives

- Displaying simple graphs

- Plotting data using matplotlib library

- Analysing data from multiple files

The mathematician Richard Hamming once said, “The purpose of computing is insight, not numbers,” and the best way to develop insight is often to visualize data. Visualization deserves an entire lecture (or course) of its own, but we can explore a few features of Python’s matplotlib here. While there is no “official” plotting library, this package is the de facto standard. First, we will import the pyplot module from matplotlib and use two of its functions to create and display a heat map of our data from the previous topic:

from matplotlib import pyplot

image = pyplot.imshow(data)

pyplot.show(image)

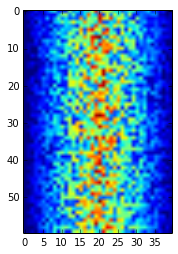

Heatmap of the Data

Blue regions in this heat map are low values, while red shows high values. As we can see, inflammation rises and falls over a 40-day period. Let’s take a look at the average inflammation over time:

ave_inflammation = data.mean(axis=0)

ave_plot = pyplot.plot(ave_inflammation)

pyplot.show(ave_plot)

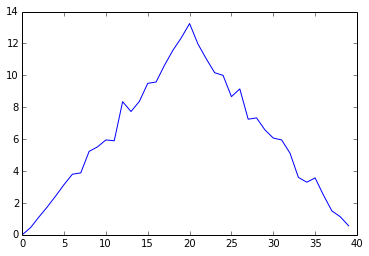

Average Inflammation Over Time

Here, we have put the average per day across all patients in the variable ave_inflammation, then asked pyplot to create and display a line graph of those values. The result is roughly a linear rise and fall, which is suspicious: based on other studies, we expect a sharper rise and slower fall. Let’s have a look at two other statistics:

max_plot = pyplot.plot(data.max(axis=0))

pyplot.show(max_plot)

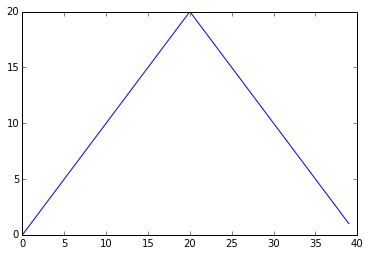

Maximum Value Along The First Axis

min_plot = pyplot.plot(data.min(axis=0))

pyplot.show(min_plot)

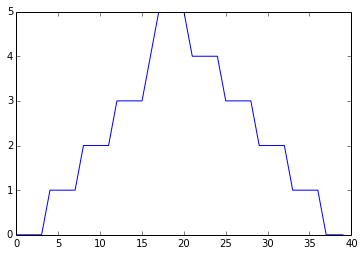

Minimum Value Along The First Axis

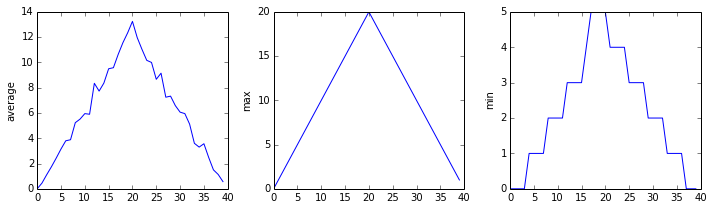

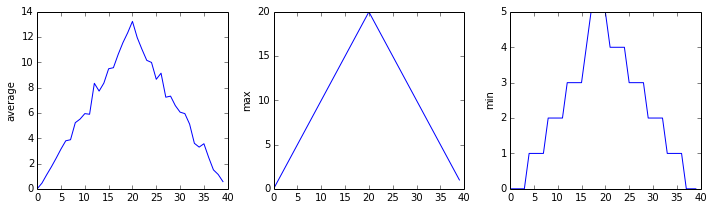

The maximum value rises and falls perfectly smoothly, while the minimum seems to be a step function. Neither result seems particularly likely, so either there’s a mistake in our calculations or something is wrong with our data.

It’s very common to create an alias for a library when importing it in order to reduce the amount of typing we have to do. Here are our three plots side by side using aliases for numpy and pyplot:

import numpy as np

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

data = np.loadtxt(fname='../data/inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',')

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(10.0, 3.0))

axes1 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 1)

axes2 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 2)

axes3 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 3)

axes1.set_ylabel('average')

axes1.plot(data.mean(axis=0))

axes2.set_ylabel('max')

axes2.plot(data.max(axis=0))

axes3.set_ylabel('min')

axes3.plot(data.min(axis=0))

fig.tight_layout()

plt.show(fig)Running the above code (present under code directory in the file three-plots.py) may throw the warning as below. If you see the warning, please ignore it.

/Users/user/anaconda/lib/python3.4/site-packages/matplotlib/tight_layout.py:225: UserWarning: tight_layout : falling back to Agg renderer warnings.warn("tight_layout : falling back to Agg renderer")

tight_layout still works by falling back to the Agg renderer.

The Previous Plots as Subplots

The call to loadtxt reads our data, and the rest of the program tells the plotting library how large we want the figure to be, that we’re creating three sub-plots, what to draw for each one, and that we want a tight layout. (Perversely, if we leave out that call to fig.tight_layout(), the graphs will actually be squeezed together more closely.)

Make your own plot

Create a plot showing the standard deviation of the inflammation data for each day across all patients. Hint: data.std(axis=0) gives you standard deviation.

Moving plots around

Modify the program to display the three plots on top of one another instead of side by side.

We now have almost everything we need to process all our data files. The only thing that’s missing is a library with a rather unpleasant name:

import globThe glob library contains a single function, also called glob, that finds files whose names match a pattern. We provide those patterns as strings: the character * matches zero or more characters, while ? matches any one character. We can use this to get the names of all the HTML files in the current directory:

print(glob.glob('*.html'))['01-numpy.html', '02-loop.html', '03-lists.html', '04-files.html', '05-cond.html', '06-func.html', '07-errors.html', '08-defensive.html', '09-debugging.html', '10-cmdline.html', 'index.html', 'LICENSE.html', 'instructors.html', 'README.html', 'discussion.html', 'reference.html']As these examples show, glob.glob’s result is a list of strings, which means we can loop over it to do something with each filename in turn. In our case, the “something” we want to do is generate a set of plots for each file in our inflammation dataset. Let’s test it by analyzing the first three files in the list:

import numpy

import matplotlib.pyplot

import glob

filenames = glob.glob('data/*.csv')

filenames = filenames[0:3]

for f in filenames:

print(f)

data = numpy.loadtxt(fname=f, delimiter=',')

fig = matplotlib.pyplot.figure(figsize=(10.0, 3.0))

axes1 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 1)

axes2 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 2)

axes3 = fig.add_subplot(1, 3, 3)

axes1.set_ylabel('average')

axes1.plot(data.mean(axis=0))

axes2.set_ylabel('max')

axes2.plot(data.max(axis=0))

axes3.set_ylabel('min')

axes3.plot(data.min(axis=0))

fig.tight_layout()

plt.show(fig)inflammation-01.csv

inflammation-02.csv

inflammation-03.csv

Sure enough, the maxima of the first two data sets show exactly the same ramp as the first, and their minima show the same staircase structure; a different situation has been revealed in the third dataset, where the maxima are a bit less regular, but the minima are consistently zero.